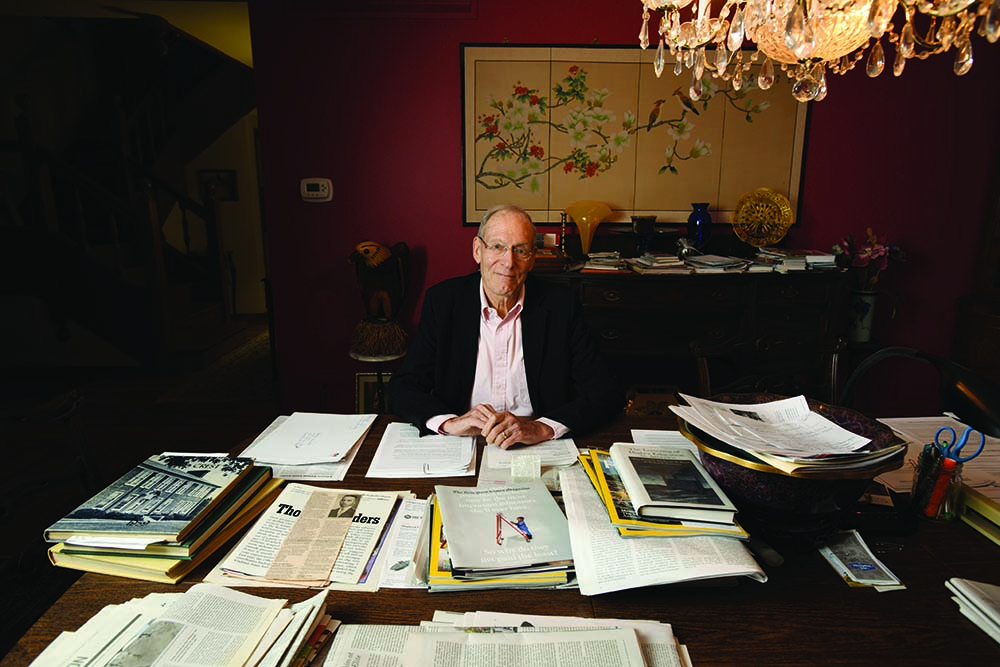

Mark Harrington '64

Making a difference in the world, for the world

The college’s $125-million AUGUSTANA NOW: A Campaign for Success in the World, for the World focuses on four student-centered goals: affordability; preparation; innovation; and diversity, equity and inclusion.

The world needs Augustana graduates, and this campaign is designed to answer that call. Here are three alumni committed to making the world a better place — in St. Louis, Milwaukee and Kenya.

MARK HARRINGTON '64: WORKING TOWARD EQUAL OPPORTUNITY

In the spring of 1964, Mark Harrington was a senior looking forward to graduation and taking a break from academics. Members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—a key civil rights organization of the 1960s—came to Augustana to recruit students to help register voters in Mississippi that summer.

Growing up in Ferguson, Mo., Harrington says he was not acquainted with black people and as a result, did not understand their experiences or racism. “It was a part of American life about which I was totally naive,” he explained.

The recruiters got Harrington’s attention. He wanted to join them to work on voter registration, but he would have to pay for his own meals, transportation and other expenses.

The Civil Rights Movement has given me much more than I have given it—I said this 54 years ago, and I still say it.

“So I left Augie, went home to Detroit where my family was living at the time and worked for a month to earn the necessary funds,” Harrington said. “While doing that, Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman, all civil rights workers, were killed in Mississippi, and that scared the hell out of me and my parents. As a result, I ended up going to St. Louis, where I had grown up, and got involved in the Civil Rights Movement there.”

In the spring of 1965—after Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala.—several ministers told Harrington they would pay his expenses if he wanted to respond to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for support. “I immediately said ‘yes,’ and a couple days later, I was in Selma,” Harrington said.

In Selma, Harrington worked with Hosea Williams, a member of Dr. King’s staff who organized the logistics of the march to Montgomery. After the march, Hosea asked Harrington and others to help him find workers to register voters in 100 predominantly black counties from Georgia to Virginia that summer. “That was the opportunity for which I was looking, and I signed up immediately,” Harrington said.

As part of a small team, he traveled to major cities on both coasts, visiting college campuses and recruiting students to work in the South.

“By far, the Civil Rights Movement has given me more than I have given it in terms of understanding American culture, society and politics and how significant race has been in shaping American institutions and psyche,” he said. “It was a non-classroom experience for which I would have paid anything.”

For Harrington, the opportunity to work with Dr. King’s staff and live primarily in black communities for a year and a half was in many ways, as he describes, an extension of his liberal arts education at Augustana.

Harrington credits his professors at Augustana—Delbrugge, Celms, Arbaugh, Parkander and many others—with helping to give him “the tools to absorb, interpret and understand all the new experiences” as well as understand the injustices black people were experiencing.

The four years after college in which Harrington was involved in the Civil Rights Movement helped guide his career path. Facing hostility and counter-protesters made him experience a side of white America that appeared disconnected from what he had known. He describes it as seeing a “totally different psychological layer” beneath the politics and economics that, ultimately, drove him toward the study of psychology.

After earning his master’s and Ph.D. in psychology at Saint Louis University, Harrington practiced psychology for 10 years before he moved into brokerage and financial planning. When he turned 60, he says “something flipped inside of me once again,” and he felt it was time to give back.

Since then, Harrington has worked with public schools, a charter school and a private elementary school in St. Louis to help provide opportunities for those children who start school with less preparation due to poverty and racial disparities.

“Democracy doesn’t require equal outcomes, but it does require equal opportunity if it is going to be stable,” Harrington said. “One of the prerequisites for the survival of our democracy is equal opportunity for everyone.”

—By Juliane Fricke

STEPHANIE ALLEWALT '04 HACKER: DESIGNING SOLUTIONS WITH THE FUTURE IN MIND

Stephanie Allewalt ‘04 Hacker never forgets the impact she can have as an urban planner. Something as simple as a street is an opportunity for meaningful change.

“We can offer better crosswalks, and bus stops, that drastically change the travel time for people who take the bus and their safety when crossing the street,” she said. “Anything we change can have a profound impact on someone’s daily life.”

And when that impact is drawn on a bigger canvas, she sees urban planning as environmental stewardship, writ large.

“I think I have Augie to thank for that passion,” she said.

Initially, Hacker thought physics and working for NASA was her goal. At Augustana, it all changed. She discovered she wanted more from the social sciences, which turned out to be geography. And the seminal moment of her vocational reflection at Augustana was choosing the environment-themed sequence that was woven into all her core courses her first year.

She remembers reading the environmental essayist Wendell Berry and faculty mentors like Dr. Norm Moline, professor emeritus of geography, who introduced her to urban planning, a specialized area of geography, and showed her how big it could be.

I have the chance to revitalize, not demolish; sustainably change, not waste.

It represents “the ultimate profession,” she said, having a scope so broad, “we actually work everywhere, setting goals, developing strategies, envisioning the past, present and future.” Environmental stewardship was already part of that conversation, and for Hacker, it’s now integral to every project.

“The whole notion is that, to be sustainable, the environmental part of sustainability is paramount,” she said. “I have the chance, alongside others, to make our paradise. I can build consensus around a vision of what we need and want, and then ‘work the plan’ to make it happen. I have the chance to revitalize, not demolish; sustainably change, not waste.”

While earning her bachelor’s in geography at Augustana, Hacker interned with Rock Island’s planning department for more than a year, flourishing in the world of neighborhood redevelopment, historic preservation and downtown revitalization. After graduating, she worked on community development with AmeriCorps in Baltimore, Md., before returning to the Midwest to collect a master’s in urban planning from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She later taught as an adjunct professor at UW-Milwaukee’s School of Architecture and Urban Planning.

Today, she works in the national headquarters of GRAEF, a full-service engineering, planning and design firm. As one of GRAEF’s senior planners, Hacker leads the firm’s Planning + Urban Design Group, and much of her work is spent under contract as the economic development director for the City of South Milwaukee.

In all her endeavors, the idea of urban planning and environmental stewardship is closely connected to a sense of community. In any place, she says, the people who occupy that place can determine its rise or fall. She recalls a recent project that was deeply rewarding in how it affected the people involved.

It concerned a part of inner-city Milwaukee that was withering from neglect. Most of the remaining residents were elderly, with little hope to rejuvenate the neighborhood they had called home for most of their lives. With the City of Milwaukee as a sponsor, Hacker arrived with GRAEF to help them develop a strategic plan. “It was achievable,” she said, “and they felt like they owned the world because they could take it on. They could protect the neighborhood that they loved so much, that contained their entire life experience.

“You can work hard for yourself, but you can only be successful if you’re working hard for others, too. What I find in urban planning is an opportunity to participate in a world of people who care very deeply about what kind of world we’re leaving for the next generation. That’s what’s driving us.”

Hacker also wants to help ensure Augustana is there for the next generation to experience what she did, and discover the same kind of passion she found.

“I have listened to former students and alums, and the majority say that Augustana provided them with a home in the time they needed it the most, in order to figure out what they were going to do with their lives,” she said. “Augustana does that in a very critical way. I want to do everything I can to support that, to see Augustana not only maintain this critical role, but to see a forecast for its growth.”

—By Jeff Moore

NELLY CHEBOI '16: FIGHTING POVERTY WITH TECHNOLOGY

Nelly Cheboi ’16 has always dreamed of helping the people from her home country of Kenya. That’s why she has spear-headed a project to ship laptops there to promote education in technological literacy.

After graduating from Augustana with degrees in applied mathematics and computer science, Cheboi decided her best weapon to fight poverty in Kenya was with technology.

“We have kids like me in Kenya who have never seen a laptop or computer or used one,” Cheboi said. The easiest, best way to a better job and a better life, she believes, is through computers.

But this technology isn’t available for most Kenyans, which is why Cheboi is focusing on teaching computer literacy skills. “I want to give [Kenyans] something that will make them self sufficient...if you give them a skill, then they can help themselves.”

Rather than waiting for somebody to help, Cheboi decided to blaze the trail herself. By her junior year at Augustana, she was able to raise enough money through her own work and donations to begin construction on an all-ages school in Kenya—Zawadi Preparatory—and hasn’t looked back since. “I kept raising money and added electricity to [the school], and ever since then, I’ve been collecting laptop donations.”

Cheboi’s request for laptops was heard by Shawn Beattie ’94, education technology manager working in ITS at Augustana, where Cheboi had worked as a student. ITS combed through its stock of rental laptops and selected a group that were out of warranty to be donated.

In her free time from her engineering job at ShipBob, Inc., Cheboi made the necessary repairs to the computers, then installed three terabytes of information from Wikipedia on each laptop because there would be no access to the internet in Kenya. Then, last July, she flew to Kenya and delivered the computers to the students herself. Her sister teaches at the school.

“Nelly is very driven and doesn’t give up,” Beattie said. “We saw that when she worked here in ITS, and she has continued down that track as an alumna.”

Inspired as a child to be a pilot by watching planes cruise in the sky over her home, Cheboi was taken with the idea of “flying out of poverty” and into a better life for her and her family. This dream, however, faded when Cheboi experienced her first flight from Kenya to the United States to attend Augustana and abruptly realized that flying was not for her.

Students in Kenyan using donated computers.

The problem, Cheboi explained, is that Kenyans just don’t have enough access to the world to begin developing their dreams. Had she met a pilot or learned about the job, it would have changed her path sooner. Instead, “I was just chasing the wrong dream.” Her hope? To expose Kenyans to the rest of the world and give them the tools they need to better themselves.

“I grew up in poverty,” Cheboi explained. “When I was 9, I would try to go and find food, scavenge—we lived right next to a hospital—so I would go to the trash cans and collect enough oil to fry one vegetable.” She feels that shouldn’t have to be somebody’s childhood, and has since devoted her energy toward ensuring others can grow up more comfortably than she did.

Beattie wasn’t wrong about Cheboi’s drive. Since donating the first lot of laptops, she has purchased more land on which she plans to build an expansion to her school—the design of which will be based on Augustana’s Olin Center. She continues to collect laptops and plans to ship more to Kenya soon.

Editor’s update: Since this aricle was written, Cheboi and Tyler Cinnamon have incorporated a nonprofit called TechLit Africa. Their mission is to foster a more technologically literate Africa. Augustana First Lady Jane Bahls is a member of TechLit Africa’s board. Cheboi and Cinnamon have collected 300 computers, some from Augustana and others from companies in Chicago. Their goal for this year is to build 10 computer labs in Kenya. Cheboi will be moving to Kenya later this spring to launch the 10 labs as a full-time endeavor.

—By Jack Harris ’20/Writers Bureau