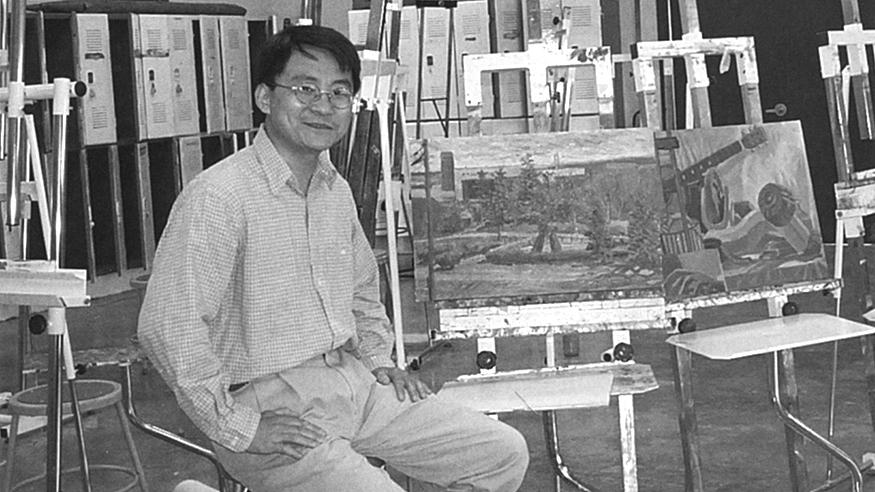

Peter Xiao moved from China to attend college in the United States in 1980. He joined Augustana's art faculty in 1989.

A father’s son makes his connections

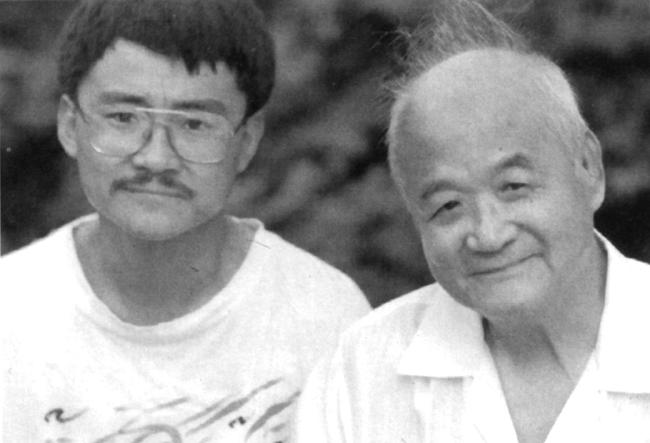

Peter Xiao with his father, Xiao Qian, in 1991

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the Augustana College Magazine, Summer 1999.

When Peter Xiao learned his father was near death in late 1998, he immediately flew to his homeland to be at his father’s bedside. Xiao Qian, one of China’s best known writers, never regained consciousness before passing away four days after his son’s arrival.

As often happens with adult children who suddenly lose a parent, Xiao is becoming aware of how enormously indebted he is to his father, the man who nurtured him as a child and the man whom the Chinese people and scholars around the world revere for his writings and translations.

“You feel the passing on,” said Xiao, 43, an associate professor of art at Augustana. ‘I’m belatedly making the connections. I realize now that all that I do was influenced by him ... I’m still absorbing that.”

Xiao Qian lived a life that spanned two civilizations, two ages and countless upheavals. He was 89 when he died. Noted authors, celebrities and Chinese dignitaries, including Premier Zhu Rongji, attended or sent wreaths or commemorative banners to his funeral.

The following excerpt from the obituary in The Times of London gives one a sense of the rich, yet difficult life Xiao Oian led:

Xiao Qian was one of China’s finest postwar literary talents: a man who was sent to labour camps by Chairman Mao for his dissenting views, and was later responsible for translating James Joyce’s Ulysses into Mandarin.

Yet before the dawn of Red China, “Hsiao Chien” (the old spelling of his name in English, to which he reverted in the 1980s) was as well known in Britain as in China. Pilot Press and George Allen & Unwin printed four books of his short stories and essays in the 1940s, including Spinners of Silk, Etchings of a Tormented Age and China But Not Cathay. His romantic eye for every ethnographic detail that made Old Peking great, the lyricism of his well-made prose, and his subtle empathy for the downtrodden (the stratum of his birth) in a society where poverty itself was shameful, established him as a cultural intermediary.

Xiao’s stories are a permanent contribution to fiction about China, scarcely equalled by Chinese writers today. But he gave up fiction for journalism. Reporting on the Second World War in Europe for newspaper readers in China, he sought out the same kinds of human dignity that had moved him at home....

He originally came to England to study at Cambridge and could have had a safe career there as a Chinese teacher. Instead, welling up with patriotism after China “Stood up” in 1949 against the same Anglo-American world he knew from the inside, he went home to serve the revolution. He enjoyed brief periods of useful service as a translator, but it soon emerged that his views were not in harmony with the new China. Many of his years were spent in internal exile, in labour camps for “Rightist” thought-offenders.

Memories from their time together in the labour camp, which involved converting a lake into a rice farm, are what Xiao and his father shared the last time he saw his father alive. It was November 1998. Xiao was visiting China as a teacher with Augustana’s Asian Program. He spent the last few days of the trip with his parents.

On his final night in Beijing, Xiao stayed with his father, who suffered from kidney disease, in his hospital room. Although Xiao Qian was frail, Xiao didn’t anticipate the call he received two months later. Nor was he ready to lose the one person in this world with whom he felt the strongest bond.

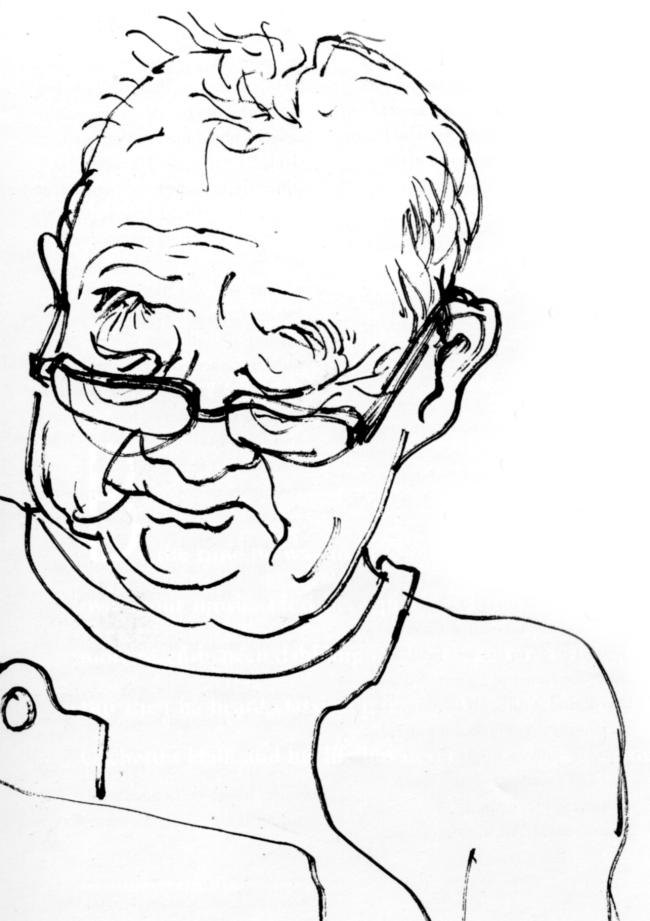

A sketch Peter Xiao drew of his father in 1996.

Although Xiao seriously considered literature as his own career, he switched to painting in the early 1980s while a student at Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. In a way, he says, his move from literature to painting was similar to his father’s decision to become a war correspondent in 1944, traveling with the U.S. Seventh Army in France and Germany.

“My father made his early fame as a fiction writer, but he was not cut out to be a scholar inside a library,” Xiao said. “He left a secluded Cambridge campus to go to the war field. He chose the career of a journalist and later found it difficult to return to fiction-writing. He found journalism 'physical and exciting.'

“I feel painting is more about embracing life, living in the present,” Xiao continued. “Art is more physical to me, especially when I’m working with a large canvas. I would choose writing over literary interpretations but both are more of the mind; art is more of the body.”

His difficulties with mastering a second language also made painting more inviting, not to mention that he found the visual art medium less personal. “Images are less biographically anchored than the writing I was doing,” he said. “Whatever you do comes from your own experience, and I wasn’t that comfortable in showing that.”

It might have been a combination, he said, of the limits he felt as a writer and an Oriental sense of modesty and privacy.

Ironically, one way Xiao is dealing with his father’s death is through writing. “It feels good to write down my personal memories of him,” he said. And Xiao has allowed his reminiscences of his father to be made public. His highly personal essay, written in Chinese, will be published in Hong Kong and China.

One of his earliest memories of his father is of the countless hours he spent with him as a boy. “He helped with my writing and my English when I was young,” Xiao said. “He was good at encouraging my artistic interest even though he claimed he couldn’t draw a circle.”

As an editor, Xiao Qian nurtured young artists, befriended many, and compiled a collection of English woodcuts for Chinese readers. He was an avid fan of classical music and art song form. He even translated and helped stage "Peer Gynt" by Henrik Ibsen.

Through these early introductions, Xiao gained a lifelong passion for the arts.

As a professor, Xiao strives to nurture his students in much the same way his father helped him. He sees college students as less informed or skilled but more receptive and energetic — a state which he finds enviable. “But there are many things that distract them; they may not recognize the need to seize the day and take in the most important experiences,” he said.

“Finding the talent or early tendencies of a young person and then trying to direct it ... that is what we do in education. And I relate it to my own growth which was nurtured by my father.”

Again, an excerpt from Xiao Qian’s obituary in The Times of London:

With the thawing of the Cultural Revolution, Xiao devoted much of his time to composing essays reflecting on his experiences: his apprenticeship at the Dagong Daily, before the paper turned communist; his old friendship and correspondence with E.M. Forster (and the shame of having burnt Forster’s letters during the Cultural Revolution); canards about his days in England that he as a “Rightist” lost the opportunity to rebut; his love of Western literature and art, vet another offence; and his sympathy with the people of London who had become enemies. These reflections were finally gathered in his autobiography, Traveller Without a Map.

In his later career he helped to translate a number of works into Chinese, among them Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, Herman Wouk’s The Winds of War and the memoirs of Harold Macmillan. In 1994 he and his wife, Wen Jierwo, together translated Ulysses.

Two western writers whom Xiao Qian befriended and admired, Edgar Snow and E.M. Forster, may have infuenced his choice as a young man of art for human cause or transformation over art for art’s sake. Some of Xiao Oian’s letters from Forster which survived dwelled on this very topic.

What Xiao finds fascinating is that his father at the age of 80 and his mother spent “four good years” translating "Ulysses," when so many years before, Xiao Qian had written that James Joyce’s style of writing would be a “literary dead end” in Europe and China.

In a letter to Xiao last year, his father wrote: “Not much time is left, but I still wish to leave behind some worthwhile things....” After his survival in China’s struggles two decades ago and toward his own life’s end, Xiao’s father, and his mother, gave Joyce’s work its deserved worth and indeed made it popular in China.

Xiao too, has struggled with this question regarding art, but has arrived at a place where he feels comfortable in his own painting. “Art with a human connection; that’s what I find most fulfilling,” he said.

Xiao remembers a conversation he had with his father in 1983 on the topic of art for art’s sake versus functional art. “He was apparently worried about the Western Modernist influences that I had come under, influences that had engaged his own youth," Xiao said. "We also talked about the role of one’s cultural roots in one’s art. In my case, it was the shortage of ‘Chineseness’ in my art.”

Since then, he has realized that the discussion was a disguise for what his father really wanted: for his son to return home to China.

Prior to this conversation, another veteran Chinese writer, Ding Ling, told Xiao during a visit to Iowa City that he should return to China to continue his painting. “That's the struggle. That's life. There's your source of creativity,” she told Xiao.

He didn’t return. He didn’t want to live and work in a country that had punished his father — and many others — for thinking and acting freely.

Xiao came to America to study in 1980 with the help of poet Paul Engle, the founder and director of Iowa’s International Writer’s Program in which his father participated as the first Chinese writer the year before. The time he spent in this country before coming to Augustana helped him assimilate American culture and build his career as an artist.

“It is at Augustana that I began to give back what this new country and friends have given to me,” he said. His experiences of teaching in the last 10 years have taught him a great deal. His involvement with the Asian Program and faculty also has helped put him in closer touch with his cultural roots.

A course of introductory drawing that he initially designed to teach during the Asian Program became enriched as a result of his collaboration with Dr. Jen-mei Ma, an associate professor in Chinese at Augustana.

“I learn from Jen-mei, and I learn from teaching,” Xiao said. “It has put me in touch with Chinese traditions that my generation was estranged from. China is a society that is materialistically poor yet culturally rich; our students would benefit by overcoming biases and seeking out these cultural values.”

More and more, as time passes, Xiao appreciates his father's role in nurturing these cultural values and connections. And these connections, he says, are what people must use to make sense of the world and to act within it in creative ways. “Carving a space for creative outlet is what it's all about,” he said.